|

The backbone of diets and economical infrastructures, rice feeds the livelihood of 3 billion people around the globe. For many Asians, rice is viewed as food, a gift from the gods, and a part of the cultural folklore. This month, we will chronicle different varieties of rice, its nutritional value, and typical rice recipes. If you’ve never cooked rice before, you’ll want to once you learn how easy it is.

More than 89 countries plant and harvest rice. The top 10 rice-producing countries all dwell in Asia—with China heading the pack. If you were to visit each country, you would probably end up eating a different kind of rice every time. According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), based in the Philippines, there are 120,000 varieties of rice worldwide. And it takes anywhere from 5 to 10 years to perfect a new rice grain for public consumption.

Rice doesn’t start out white. The grains are grown in a plethora of colors and textures. Brown rice grains, unlike white, still have an outer coating of bran. This bran carries twice as much fiber, three times as much vitamin E, and three times the amount of magnesium than enriched white rice. Usually produced as long or medium-grains, brown rice takes more time to cook, tastes chewier, and retains a mild, nutty bran flavor. Generally not part of Asian cuisine, brown rice is a good choice for the health-conscious. Rice doesn’t start out white. The grains are grown in a plethora of colors and textures. Brown rice grains, unlike white, still have an outer coating of bran. This bran carries twice as much fiber, three times as much vitamin E, and three times the amount of magnesium than enriched white rice. Usually produced as long or medium-grains, brown rice takes more time to cook, tastes chewier, and retains a mild, nutty bran flavor. Generally not part of Asian cuisine, brown rice is a good choice for the health-conscious.

Another nutty, medium-size grain is black rice. The black bran-filled grains turn a deep purple when cooked. Cultivated in Indonesia and the Philippines, stickier varieties of black rice are used often for sweets such as rice pudding in countries throughout East Asia including Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore.

The rice world also owes a debt to Thailand, the nation that originated the planting of jasmine rice. Universally described as “aromatic,” this fragrant long-grain rice has a soft texture due to a special water milling process. Yet when cooked, this rice comes out moist and tender like medium sized grains. Available in brown and white, jasmine rice is a staple of Thai cooking—which you’ll read more about later.

One of the most wondrous things about white rice and its brown counterpart is the effect length has on preparation. The size and texture of the grains you buy can make or break a recipe; the rice you cook determines whether the dish will be considered Chinese or Japanese. Most Chinese dishes and feasts revolve around long-grain rice—where a grain’s length is three or more times its width. These grains tend to cook separated and fluffy.

Going down the scale, medium-grain rice consists of grains whose length is less than twice its width. High in starch, the grains come out moist and tender with a bit of stickiness when cooked. Medium-grains are harvested in Italy and Spain; they tend to grow in regions farther from the equator. Hence, you’re more likely to find it in European delicacies such as risotto and paella.

Short-grain rice also has a length that’s less than twice its width. The grains, when cooked, are softer and stickier than medium-grain. In Japan, sushi is only as good as the short-grain, sticky rice that forms its essence. Sticky rice has numerous uses. While it is also utilized for desserts, sticky rice is an integral part of every meal in regions of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. In addition, sticky rice is a primary source for brewing rice-based alcohol like sake.

Another type of rice essential to pan-Asian cuisine is glutinous rice. Although it doesn’t contain any gluten, this short-grain, starchy rice becomes quite sticky and dense when cooked. This rice is labeled as sticky, waxy, and sweet. Generally used for desserts, glutinous rice is in demand for making little cakes in Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In China, this rice is used to make, jung, which can be described as a Chinese tamale. Glutinous rice wrapped in giant bamboo leaves, these “tamales” can be sweet or salty, depending on what your tastes are. In jung, rice is folded with ingredients such as mung beans, salted duck eggs, or Chinese sausage.

Steamed, boiled, fried, baked, microwave—white rice can be prepared numerous ways. It’s fine if, unlike most Asian households, you don’t own an electric rice cooker. Preparing rice on the stove is quite easy. First, rinse rice two to three times. Then place rice and water in a saucepan. Generally, 1 ½ to 2 cups of water is needed for every one cup of rice. Cook covered on high heat until water is boiling (Hint: good indicator is to see if water level appears same as rice). Then reduce heat to low, allowing the rice to simmer for 30 minutes. Then remove the saucepan from the heat and let the rice stand, covered, for 10 minutes. Remove the rice and fluff it with a fork before serving.

Long grains are also essential for rice porridge, a renowned Asian comfort food. Known in Chinese as jook, the porridge gets its runny-oatmeal consistency by being cooked with more water, boiled longer, and flavored with chicken stock. You can top bowls of jook with anything from meatballs, thousand-year-old eggs, fish, and cilantro to garnish. In many Asian countries, especially China, breakfast consists of steaming porridge with a piece of fried bread. In fact, vendors often sell the porridge from huge pots suspended from bamboo poles.

Long-grain rice, such as jasmine rice, is popular for making fried rice in many cultures. In Thailand, this dish is prepared the same way except with cold, cooked jasmine rice. First, cut a fresh pineapple lengthwise and scoop out the pineapple pulp. Then stir-fry oil, salt, and garlic in a wok until the garlic turns a light golden brown. Raise the stove’s heat to high and throw in shrimp and chicken. Once those are cooked, you can crack a couple of eggs, break up the yolks but then allow them to set undisturbed. Stir in crab paste and ketchup, add green onions, four cups of loose rice, and fish sauce. Mix everything well, season the rice and add the pineapple pulp. Meanwhile, bake the pineapple shells in the oven at 400°F for 10 minutes. Remove them and once they’ve dried out, you’ll have two festive serving dishes for your rice.

If it’s a Japanese sushi bar you’re craving, you can roll your own sushi at home. Start with 2-3 cups of short-grain rice—washed and left to drain for 30 minutes to an hour. Cook short-grain rice in a sauce pan or rice cooker. Meanwhile, make a dressing comprised of ½ cup of rice vinegar, 4 tablespoons of granulated sugar, 2 tablespoons of hot water, and 1 ½ -2 teaspoons of salt. Keep dressing cool. After the hot rice has cooled down, pour in the dressing a little at a time while gently stirring the rice as though tossing a salad. Taste the rice until you’re satisfied with the amount of dressing. Cover the rice in a cool place until you’re ready with your preferred toppings. If you’re nervous about rolling sushi, consider getting one of our bamboo sushi mats. Inexpensive yet instrumental, the mat will help nori seaweed wrap around rice and whatever ingredients you throw in.

If it’s a Japanese sushi bar you’re craving, you can roll your own sushi at home. Start with 2-3 cups of short-grain rice—washed and left to drain for 30 minutes to an hour. Cook short-grain rice in a sauce pan or rice cooker. Meanwhile, make a dressing comprised of ½ cup of rice vinegar, 4 tablespoons of granulated sugar, 2 tablespoons of hot water, and 1 ½ -2 teaspoons of salt. Keep dressing cool. After the hot rice has cooled down, pour in the dressing a little at a time while gently stirring the rice as though tossing a salad. Taste the rice until you’re satisfied with the amount of dressing. Cover the rice in a cool place until you’re ready with your preferred toppings. If you’re nervous about rolling sushi, consider getting one of our bamboo sushi mats. Inexpensive yet instrumental, the mat will help nori seaweed wrap around rice and whatever ingredients you throw in.

In the Philippines, rice is generally consumed three times a day. It is customary to serve plain boiled rice and mix it with a dish like Chicken Adobo. But, Filipinos also use glutinous rice for delicacies like bibingka, a coconut rice cake. Because of centuries of colonization by Spain, Filipino cuisine also has Spanish roots. Fortunately, this influence has made for some delicious fare. A favorite dish in some provinces is a Filipino twist on the Spanish paella, using coconut milk, fish sauce, and both glutinous and long-grain rice.

When you’re preparing rice in a pot on the stove, you’ll end up with a thick cake-layer of rice— ¼ inch to ½ cm thick—stuck to the bottom. Indonesians call this layer intip. Some people like to dry the intip in the sun or oven, break it into smaller pieces for deep frying, and then salt them for a snack. In Korea, people will pour water on this stuck rice and then boil it. They then drink the resulting hot rice water, soong nung, as an aid against indigestion.

In terms of nutrition, rice has a lot to offer—no matter what those no-carb diets preach. Although 80 percent of white rice is starch, each grain contains fair amounts of complex carbohydrates, proteins, calcium, fiber, and vitamins—such as thiamine, niacin, iron, riboflavin. White rice also comes with almost no fat, low sodium levels, and no cholesterol. Still, rice, like any food, should be enjoyed in moderation.

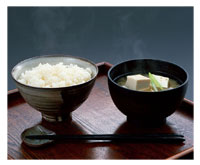

For Asian cultures, nothing beats white rice. Serving the grains plain in a separate bowl—with spices and salt on the side—is regarded as the ultimate symbol of purity. Although most Asian restaurants will provide a fork and a plate, try eating with chopsticks and a bowl on your next meal out. Or better yet, peruse Mrs. Lin’s numerous ceramic and porcelain rice bowls available in different color schemes and patterns—in the tableware section. Also, take a look at our entire chopsticks section. We offer more than 200 kinds of chopsticks made from all sorts of material—bamboo, lacquer, plastic, and wood. Some have specially tapered edges to aid in picking up food. Check out our cookbook section so you can have rice recipes on-hand all the time. Remember, a meal isn’t quite as nice without rice. For Asian cultures, nothing beats white rice. Serving the grains plain in a separate bowl—with spices and salt on the side—is regarded as the ultimate symbol of purity. Although most Asian restaurants will provide a fork and a plate, try eating with chopsticks and a bowl on your next meal out. Or better yet, peruse Mrs. Lin’s numerous ceramic and porcelain rice bowls available in different color schemes and patterns—in the tableware section. Also, take a look at our entire chopsticks section. We offer more than 200 kinds of chopsticks made from all sorts of material—bamboo, lacquer, plastic, and wood. Some have specially tapered edges to aid in picking up food. Check out our cookbook section so you can have rice recipes on-hand all the time. Remember, a meal isn’t quite as nice without rice.

|

|

|

OUR 2005 NEWSLETTERS

Full Of Fortune

All About Sushi (part II)

Secret Lives Of Geisha

Specialty Japanese Cookware

Rice The Golden Grain

Summer Wedding Gift Guide

Azuki Beans

Washi Paper Production and Uses

Symbols of Happiness and Longevity in Asian Culture

Bamboo – A Versatile Plant

Symbolism in Asian Motifs and Patterns

Fortune Cookies: The Real San Fransisco Treat

NEWSLETTER ARCHIVES

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

MAY WE SUGGEST:

Bamboo Sushi Mat (8515)

Eight-Inch Rice Paddle (8521)

|